The air we breathe can sometimes contain tiny particles called particulate matter (PM). These particles come in different shapes and sizes and are made up of hundreds of different chemicals. Some are very small, smaller than 2.5 micrometers. They are referred to as PM2.5. You can't see these particles, but you can inhale them.

As a group, PM2.5 is responsible for most pollution-related health problems in the United States. But not all PM2.5 are created equal. Some are particularly toxic, and where you live can make a big difference in the quality of the air around you.

NIH-funded research has turned up some important findings about air quality’s effects on different communities.

Pollution and racial segregation

Many communities face an unfair burden by poor air quality, with communities of color often facing the highest exposure to PM2.5. This disparity is linked to racial residential segregation, where people of different races live in separate areas often due to social, economic, or discriminatory factors. When these areas are exposed to more pollution, it can increase health risks for the people who live there.

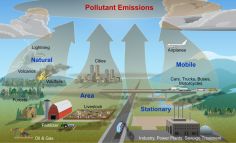

A 2022 study wanted to understand how the most toxic components of PM2.5 are distributed across different communities. They found that the air in racially segregated, predominantly Black counties not only had higher levels of PM2.5, they also had higher concentrations of toxic metals compared to air in racially integrated communities. The highest levels of these toxic metals were mostly those generated by humans (for example, from industrial activities, waste burning, and car exhaust).

Exposure to certain toxic metals can lead to cancer. It can also damage the brain and nervous system. This means many communities of color are breathing air that's not just polluted, but loaded with harmful chemicals, too.

There is hope: For one, cleaner fuel regulations can go a long way toward improving air quality. This can reduce disparities in pollution and improve health for communities most at risk.

Air pollutants and asthma attacks in urban youth

Asthma is a chronic lung condition that creates inflammation of the airways. It can cause coughing, wheezing, or shortness of breath and make breathing difficult. Severe asthma attacks may require emergency room visits or hospitalizations. Triggers include:

- Environmental allergens (such as pollen, dust mites, and pet dander)

- Viral infections (such as cold, flu, and COVID-19)

- Poor air quality

Kids in lower-income urban neighborhoods are more likely to experience frequent asthma attacks. A study discovered a link between outdoor air pollution and asthma attacks in children and teenagers living in those areas.

For this study, researchers followed more than 200 children and teenagers in nine cities across the United States. They found a connection between nonviral asthma attacks (attacks that are not caused by respiratory viruses) and moderate levels of two air pollutants: ozone and fine PM. These pollutants are often highest in areas with heavy traffic and industrial activity.

Researchers also saw that those children had changes in the genes that play a part in airway inflammation and linked those changes to higher levels of air pollution. This could reveal how pollution affects the body and may lead to attacks.

This study is one of the first to connect specific air pollutants to nonviral asthma attacks. It highlights why clean air is so important for human health.

A concerning link between pollution and dementia risk

A recent study found a connection between air pollution and the risk of developing dementia as we age.

The data in this study were collected as part of the Health and Retirement Study, which follows older adults’ health over time.

Researchers at the University of Michigan compared information about air quality to health data from more than 28,000 adults ages 50 and older across the United States. They found a troubling link between long-term exposure to PM2.5 and increased risk of dementia.

People who developed dementia were more likely to live in areas with higher levels of air pollution. They were also more likely to be non-White and of lower socioeconomic status. People exposed to air pollution from farming and open fires were most at risk. These findings suggest that reducing air pollution, particularly from these sources, could reduce the chances of developing dementia later in life.