Even after decades of research in the field, George F. Koob, Ph.D., is still learning new things about alcohol, its overall effects on human health, and alcohol use disorder. He has been Director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) since 2014, and he wants everyone to know what the institute has to offer. Dr. Koob talked to NIH MedlinePlus Magazine about his career, the neuroscience of alcohol use disorder, different NIAAA resources used to understand and treat this condition, and what he wishes more people knew about alcohol’s effect on the body.

Tell us about your background and what brought you to the field of alcohol and drug addiction research.

A long time ago, in a galaxy far, far away, I wanted to be an ethologist (someone who studies animal behavior). I went to the Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health to study ethology, but my advisor was working on brain stimulation reward.

If you’ve ever seen a rat press a lever 100 times per minute to stimulate its medial forebrain bundle (the part of the brain that generates pleasure sensations)…I was hooked. I like to say that I spent the first half of my career studying why we feel good and the second half of my career trying to understand why we feel bad. I became interested in alcohol and other drugs of addiction and how it affects the brain.

How did you become Director of NIAAA?

Fast forward a few years to 1977, when I worked as a staff scientist at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies and joined the NIAAA-funded alcohol research center led by Dr. Floyd Bloom. We then moved to Scripps Research in 1984 where we expanded to a major program on the neurobiology of alcohol use disorder that is still ongoing there. I became Director of the Alcohol Research Center at Scripps and Director of a branch of the NIAAA-supported Integrative Neuroscience Initiative on Alcoholism. This initiative seeks to understand the molecular basis of alcohol use disorder. Then, when the search for the Director of NIAAA was announced in 2013, I applied.

I had reached a stage in my career where I felt like we could do more to translate the basic research into [information that] people need. That was probably one of the guiding forces that moved me to want to work at NIH. And then when I interviewed with the fantastic institute Directors that were already at NIH—that was another plus. I met Dr. Anthony Fauci, and Dr. Nora Volkow and I already knew each other. There were just so many wonderful, unbelievably smart people, and I thought, “Wow, this has got to be really exciting!”

How is NIAAA communicating more alcohol addiction research to the public?

In the last few years, we’ve really put a focus on making evidence-based information about alcohol available to the public. There’s a big gap between what we know scientifically about alcohol and the public’s understanding about alcohol, and even health care professionals’ understanding about alcohol. It took me a little while as Director to get my head around what we knew, and I realized the extent of what we know and how little of that had been translated [to the public]. That includes screening and intervention, referring someone to a primary care doctor’s office or any other health professional’s office for treatment, and even understanding what a standard drink is. Those are the things that we have been missing and are the things that we’ve basically addressed since I became Director.

Translating evidence-based information about alcohol remains a challenge. We have learned an enormous amount about where alcohol works in the brain and what circuits are activated in different stages of the addiction cycle. I think, slowly but surely, we’re using that information to develop better treatments for alcohol use disorder.

NIAAA is writing a new 2023–2027 Strategic Plan. How will this continue the work of the previous plan?

In the last five years, we created websites such as the NIAAA Alcohol Treatment Navigator, which provides people with not only information about what an alcohol use disorder is, but also the spectrum of treatment for alcohol use disorder. You can also type in your ZIP code and find the closest treatment facility.

Prior to my arrival at NIAAA, they developed the CollegeAim Alcohol Intervention Matrix to help universities address alcohol issues among students. I suggested that we do similar things in other areas, including for other age groups, so that will continue in the new strategic plan.

Last year, we launched the Healthcare Professional’s Core Resource on Alcohol. It explains everything you wanted to know about alcohol. It’s aimed at primary care doctors, but it can be used by everyone, from a pharmacist to a nurse practitioner, a clinical psychologist to a board-certified addiction medicine specialist. We’re going to be promoting that in the new strategic plan. We want everyone to know about this core resource on alcohol, and not just in health care—we’ve also sent it to every medical school in the country. We hope that we can influence medical school training and residency training. Those are some things that can directly help the public, and they’re some of the things I’m most proud of.

Dr. Koob, back row, fourth from left, stands with his lab group in the Neurobiology of Addiction Section of the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, in 2022.

How is NIAAA addressing health disparities in its research? How is NIAAA promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in the biomedical workforce?

We’ve always had an emphasis on diversity, equity, and inclusion, but that’s become an overriding theme at the institute—as it is for all of NIH. And we’re working hard to expand our work in this area. We really believe that it will increase creativity, our relevance, and help people get better treatment.

Our mission is to provide evidence-based information about the diagnosis, prevention, treatment, and evaluation of alcohol use disorder and about the overall health consequences of alcohol. To only study one cultural group or type of individual or one sex or one gender is just not acceptable. There are so many individual differences in how we respond to alcohol and our vulnerability to the [harmful] effects of alcohol. That’s one area that has shifted in priority for us.

Another is training young people and moving young people along in our field. That’s another big area that we put a lot of emphasis on, and we will continue to do so.

What is something that you wish more people knew about alcohol?

Alcohol use disorder is not just a brain disorder. It’s a body disorder. I think the public has limited knowledge about alcohol, to be honest. Even the basic [questions]: What is a standard drink? What does “moderate drinking” mean? And what are the U.S. dietary guidelines for drinking alcohol?

[Alcohol] is a social lubricant. It is used widely in the United States. Around 70% of Americans drink alcohol at one time or another. But what people don’t realize is that having more than one or two drinks, depending on one’s individual circumstances, can produce basically toxic effects. Even one drink a day can increase a woman’s risk of breast cancer, for example.

NIAAA defined binge drinking many years ago. I was part of the national advisory council to NIAAA [at the time] that helped define it, and I think it’s been very useful, and not only for research purposes. It’s been adopted by everyone, from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Binge drinking is reaching, basically, the blood alcohol level [to a point where] you could be arrested for driving under the influence. I don’t think people realize that that level of drinking is very harmful to your health.

How has your personal understanding of alcohol use disorder changed since joining NIAAA?

I’ve come to realize—and it’s something we speak to the press about quite a lot—that there’s really no safe amount of alcohol. And some people shouldn’t drink at all. That is a position that I’ve adopted, certainly, in my tenure at NIAAA. I probably would have been less likely to categorically say that before reviewing all the evidence that we’ve accumulated over these last nine years, since I’ve been Director.

People who are pregnant or may become pregnant should really not drink at all. Also, individuals who, because of their genetic makeup, can experience an alcohol flush reaction (unpleasant symptoms caused by your body’s inability to process alcohol) are at an increased risk for cancer. There may be individuals who have a family history of alcohol use disorder and should know their own risk of developing the disorder.

By the way, we don’t use the word “alcoholic” or “alcoholism” anymore. Dr. Nora Volkow [Director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse], Dr. Joshua Gordon [Director of the National Institute of Mental Health], and I recently published a paper about how words matter and how the words being used in addiction and mental health disorders can increase or reduce stigma.

What emerging research in this area are you particularly excited about?

We’ll be putting a lot of energy into trying to understand what facilitates recovery. If you go into a 28-day rehabilitation facility, you might receive everything—from cognitive behavioral therapy to medications approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to yoga—[but] we don’t know what works. It could have been the biofeedback (therapy that uses electrical sensors to measure body functions) or the cognitive behavioral therapy or, for all we know, it could have been the yoga.

We’re going to be drilling down into issues like recovery, resilience, and prevention of alcohol use disorder. We’ve done a lot on the college-level prevention program. We need to look at the same age group outside of college campuses and continue to work on innovative approaches to prevent underage drinking.

Another major area that we work on, and an emphasis in the new strategic plan, is fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (harmful health conditions associated with prenatal alcohol exposure). We really need to continue our emphasis on protecting pregnant people from exposure to alcohol. And we need earlier diagnosis and treatment for those who have been exposed prenatally to alcohol to help them adapt to whatever symptoms they may have as a result.

We’re interested in studying comorbidities. Alcohol-associated liver disease has been increasing to what physicians tell me are “epidemic” proportions. Alcohol misuse now accounts for nearly half of liver disease deaths in the United States. We’re working to see how someone screened for liver problems can also be screened for alcohol use disorder. Similar efforts should be directed at all health conditions that frequently co-occur with alcohol misuse, including mental health disorders. There is also a gap in our knowledge about the negative health effects of drinking in individuals who drink at levels beyond the recommended dietary guidelines but who do not meet the criteria for alcohol use disorder.

Other exciting challenges for NIAAA include developing and applying cutting-edge technologies such as artificial intelligence, telehealth, and biosensors (wearable devices that measure blood alcohol concentration). These technologies could improve access to and quality of prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of alcohol use disorder and other alcohol-associated conditions.

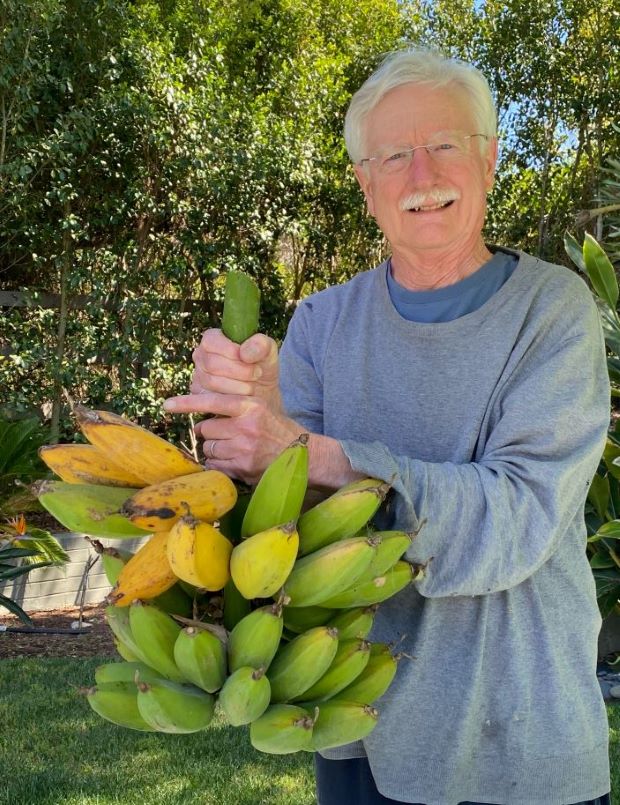

Dr. Koob grows fruit trees in Southern California.

What are some of your favorite things to do when you’re not working?

My wife and I love to travel. We love art, so when we get some time off, we’ll go to art galleries wherever we can. We hope to get to the Vermeer exhibition in Amsterdam, so that’s on our bucket list. We also enjoy warm climates where you can snorkel and do things by the shore.

I went to one meeting in Nice, France, since the pandemic started, but we hope to go back to France soon. It’s one of our favorite places to go. I speak French, and I have a number of French colleagues who allow me to practice my French when we Zoom. I grew up in Southern France near Bordeaux, so I understand that accent better. I’ve given lectures in French, and it gives me a lot of empathy for people who come to the United States and have to give a lecture in English when it’s their second language.

The other passion I have is growing fruit trees at our house in Southern California. We have about 130 different fruit trees on the property. We grow fruit year-round. It’s a lot of fun, and trees grow slowly, so for someone who travels a lot…the two work together. When you’re back in town, you can eat the fruit.