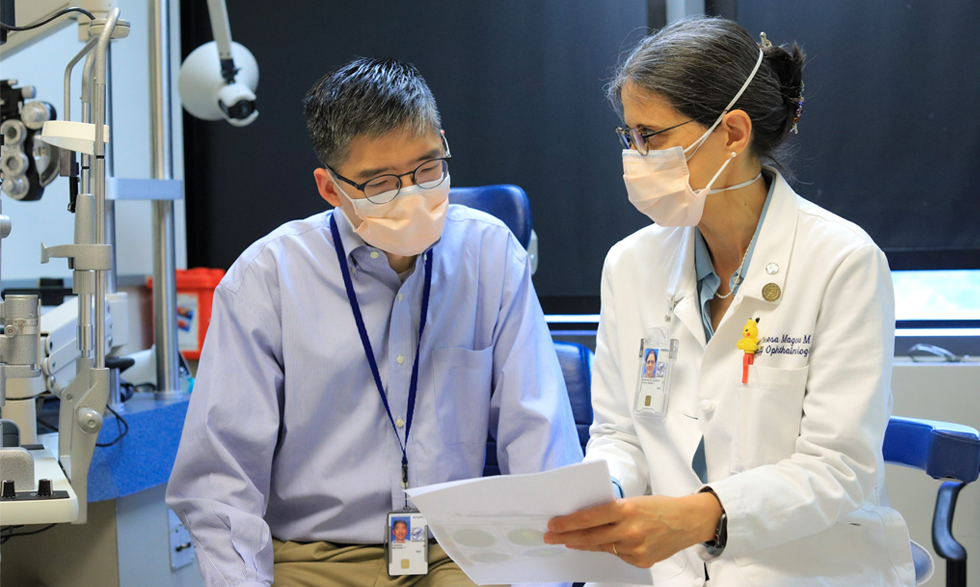

Michael F. Chiang, M.D., Director of the NEI

National Eye Institute (NEI) Director Michael F. Chiang, M.D., started his position during a strange time: In November 2020, protests over racial inequality continued across the country, and the nation was buckling down for the winter COVID-19 wave that would disproportionately affect people of color.

Dr. Chiang has worked tirelessly to meet the needs of our community by reorganizing NEI’s mission and strategy to ensure the institute’s research is accessible to those who need it most. NIH MedlinePlus Magazine chatted with him to see how things have changed almost two years into the job.

You’ve been a big advocate for DEIA (diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility) at NIH. What drives your passion for that?

My parents moved to this country from Taiwan in the late 1960s, a few years before I was born. I was born in Pittsburgh, and when I was two, we moved to Detroit because my dad got a job at Ford Motor Company. I basically spent all the formative years of my childhood in Michigan, which at that time was not a place where there were many people who looked like me.

When I trained in ophthalmology in the late 1990s and early 2000s, there were barely any ophthalmology faculty who were of Asian descent. That’s changing now, but it really gave me an appreciation for the significance of having role models and having people who look like you in supervisory or leadership positions.

I want to be able to do that, especially for younger people who come from different backgrounds, and that’s going to require some work in the world that we live in. I think we’re making progress on that compared to when I was younger, but I feel there’s a lot more that we can do with this.

What are some efforts along those lines that you’d like to see implemented at NIH or elsewhere?

I think this pandemic has exposed that we have a lot of health care disparities in the United States and that there are pockets in this country, in both urban and rural areas, that are really medically underserved. We can do the best science in the world, but if it doesn’t get to the people who need it the most, it’s not nearly as useful.

There are many diseases in this country that disproportionately affect certain populations that are the most medically underserved. For example, glaucoma disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic patients. From a delivery-of-care perspective, it’s important to have people in the health care system who the patients can truly relate to.

From a scientific perspective, we often talk about how important it is to do interdisciplinary work, where people with different academic backgrounds work with each other to think outside the box and come up with insights they wouldn’t have had on their own. I think one aspect of this that’s often underappreciated is that people who come from different personal backgrounds have different views of the world, so it’s so important to have a diverse group of people who work together on these projects and contribute new ideas.

You’ve made those changes a cornerstone of NEI through a new mission statement. How did that change?

When I started this position, looking carefully at our mission was one of the first things I did. I used to think mission statements were tools used by bureaucrats and bean counters, but I’ve seen firsthand the impact they can make in an organization when you use them to create a North Star.

Our mission statement had not changed since NEI began in 1968. It had to do with protecting and prolonging vision and with managing the special needs of people who have visual impairments. We spent months looking at this with stakeholders within and outside of NEI, and we came up with our new mission: to eliminate vision loss and improve quality of life through vision research.

Vision is so important to people. Surveys have shown that people are really afraid of becoming blind. This is extremely stressful and a source of anxiety and depression in many patients. Vision is one of the primary ways we experience the world; it’s a major gateway to human emotion. And every single one of us will develop a vision problem, including refractive error [which makes it hard to see clearly] and cataracts, if we live long enough.

I think it’s really important to emphasize that at NEI, the research we do is not solely intended to publish papers or to fight diseases; we’re ultimately trying to fight for the people who have those diseases and improve their lives. That is why our mission statement includes “improve quality of life.” As people are living longer, I think it’s more important than ever to focus on quality of life.

We have four bullet points about how exactly we’re going to achieve our mission: drive innovative research; foster collaborations; recruit, inspire, and train talented and diverse individuals; and educate people about what we do and why it’s important.

Why do you think NEI’s research is important for our modern society when there have been so many improvements in vision treatment?

Many Americans need eyeglasses; refractive error is one of the most basic things that can go wrong with vision. But the diseases that can blind people—things like cataracts, macular degeneration, glaucoma, and diabetic eye disease—those things aren’t as easily reversible, and the risk of those diseases increases exponentially as people get older. This is an enormous public health problem as our entire population gets older.

Vision research also has made a really tremendous scientific impact to methodological research, which we can apply to other parts of the body and other fields. For example, the first self-driving artificial intelligence system in medicine was for diabetic eye disease because there’s so much data we can gather when studying the eye compared to other systems. The first gene therapy approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for an inherited disease [a disease that’s passed down from parent to child] was for a retinal degeneration [an eye disease that causes the retina to break down] that causes babies to go blind because you can analyze and deliver those therapies very precisely in the eye.

You were an engineer before you became a doctor. What got you interested in science, and what made you pivot to medicine?

I grew up in a family where almost everyone was an engineer. The toys I had as a kid often had an engineering bent, and my father was the stereotypical engineer who couldn’t help taking apart every mechanical or electrical device to try to make it better… even though he often made them worse.

When I went to college, I never seriously considered studying anything except electrical engineering. I loved doing that—I was at Stanford University in Silicon Valley, and it was a very exciting place to be. I spent one summer working for a startup company that built cardiac ultrasound machines, and I spent another summer working in a lab at the medical school, where my job was to write computer programs that analyzed images from cardiac ultrasound machines to diagnose heart disease.

It fascinated me that you could build a machine and treat people with it. That’s what made me want to go into medicine—I thought I would build machines and use them to help treat people. I originally wanted to be a neurosurgeon as I thought I could model the brain using computing devices, then operate on it. I found a lab in the division of neurosurgery research at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and it happened to be work in the rabbit retina. After working in that lab for almost three years, I became fascinated with vision science and decided I wanted to become an ophthalmologist.

What are some of your favorite things about your job at NIH?

What motivates me is the hope of making a difference. I don’t know that there’s any other place in the country where we can have the potential to make so much impact on a broad scale. What we do touches people throughout the country and potentially throughout the world. That is enormously daunting, and it’s an enormous responsibility.

What do you enjoy doing when you’re off the clock?

In August, I will have been married 25 years, and I have two daughters. Like many other people, I have struggled with work-life balance, but one of the things we’ve always done is have dinner as a family every night. I do a fair amount of traveling, and sometimes I’ll get home late or the kids will get home late, and it can get stressful trying to get everybody together. But I’ve always loved being able to connect with my family through those dinners. Also, both of my daughters have been very involved with sports, and I’ve spent a lot of time practicing with them or watching on the sidelines!

Hear Dr. Chiang talk about using artificial intelligence to improve screening and diagnosis for children with a pediatric retinal disease called retinopathy of prematurity in this YouTube video from NLM.