When the pain from sickle cell disease became too much, Kirti Dasu often went to the nearest hospital emergency room. Those days are gone.

Today the 29-year-old Syracuse University student is pain-free thanks to a revolutionary but experimental gene transfer procedure at NIH.

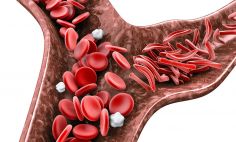

His abnormally shaped or "sickled" blood cells were replaced with normal ones derived from his own bone marrow.

Sickle cell disease is a group of inherited blood disorders. The disease creates abnormally shaped red blood cells that slow blood flow and prevent oxygen from reaching parts of the body. It can shorten lifespan, cause organ damage, and lead to debilitating pain.

"We can live free of this disease. We don't need to live in pain anymore."

- Kirti Dasu

In the U.S., the life expectancy of a person with the disease is now about 40 to 60 years. In 1973, the average lifespan was only 14 years.

Dasu has been part of an investigational NIH-sponsored clinical trial that holds great promise for curing the disease. Because of this and other sickle cell disease research like it, NIH Director Francis Collins, M.D., Ph.D. said in 2016 that a lasting cure could be only five years away.

"Genetic blood diseases are prime candidates for potentially therapeutic gene-editing approaches because a patient's cells can be easily accessed, edited, and then replaced," Dr. Collins wrote in a 2016 blog post. "Sickle cell disease is an obvious first choice, in part because the condition affects millions of people around the world—100,000 in the U.S. alone."

For Dasu, the NIH-sponsored clinical trial transformed his life.

He was diagnosed with sickle cell disease at four months of age in his native India. He even saw his younger brother die of the disease.

Dasu was able to access better medical care in the U.S. after moving here in 1999, which eventually led him to the clinical trial.

"The word miracle is very apt in my case," he says. "My mom found a pamphlet about this trial sitting on the desk in my nurse's office."

On May 30, 2017, Dasu underwent an experimental gene therapy procedure at the NIH Clinical Center on the NIH campus in Bethesda, Maryland. His recovery has been amazing. He no longer suffers from intense pain and has more energy than ever before.

"I feel like I've been granted a new life. There is a significant difference in my energy levels now," Dasu says.

More research studies and clinical trials are still needed before everyone suffering from sickle cell disease can have relief like Dasu. He still requires careful monitoring and followup in the future to verify that the procedure is working.

He encourages others to take part in clinical trials to help speed better treatments for sickle cell disease and other conditions.

Dasu's sickle cell disease experience has changed his life in more ways than one.

After graduating from college, he plans to pursue a medical career to help others like NIH researchers and doctors helped him.