Alzheimer's disease is the most common cause of dementia, which contributes to a decline in memory, thinking, and social skills. More than 5 million people in the U.S. live with Alzheimer's, which currently has no cure.

But results from a study funded by the National Institutes of Health offer a new direction for developing a treatment.

Researchers looked at a large, extended family in Colombia, South America. Many members of that family have a gene difference that causes Alzheimer's symptoms early, usually in their 40s, rather than after age 65.

Of the more than 6,000 people in the family, about 20% had this gene difference. Everyone who had it developed problems with thinking early—except one woman.

Unlike her family members, this woman didn't have symptoms until she was in her 70s. This interested the researchers, and she volunteered for brain imaging and genetic testing to help them understand why her Alzheimer's developed later.

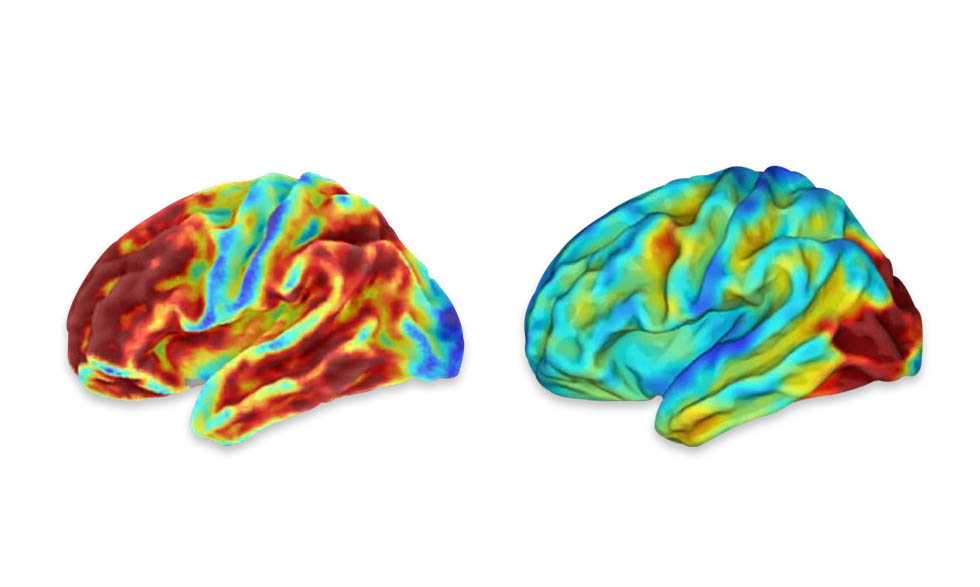

Images of her brain showed less damage than is normally seen in people with the disease. The results of the genetic testing were also intriguing. It turned out that the woman had two copies of a rare variation in the APOE gene, called APOE3ch.

This discovery could go a long way in helping to advance Alzheimer's research, for example, by mimicking how this gene variation affects the brain.

"Sometimes close analysis of a single case can lead to discovery that could have broad implications for the field," says National Institute on Aging Director Richard J. Hodes, M.D.