NIH is improving prosthetic, or artificial, limbs so that they can work better and feel more natural to patients.

Using vibrations and a complex, computerized interface between patients' brains and limbs, the team of researchers was able to trick the patients' brains into moving their prosthetic hands.

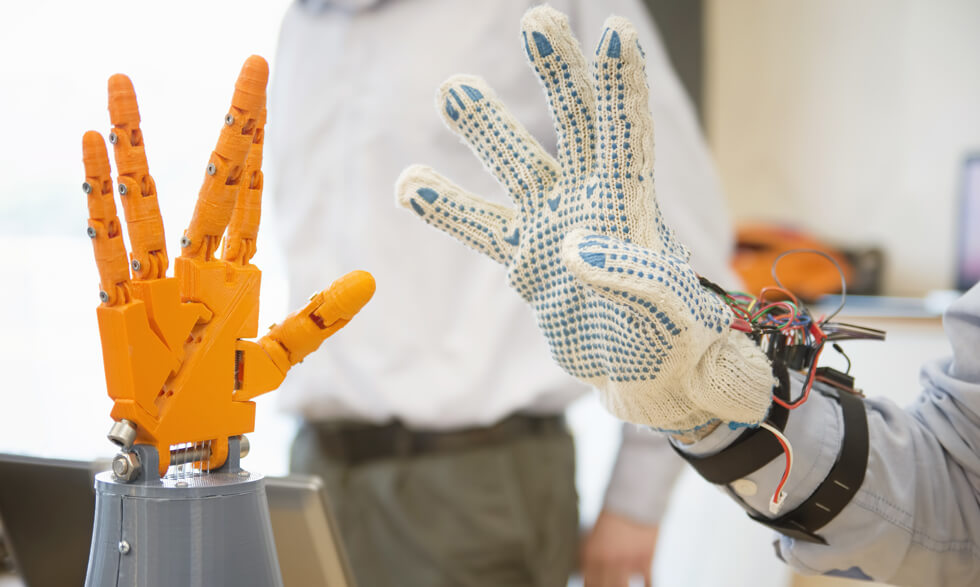

In the small group of patients with limb loss, a surgeon redirected the nerves for the missing part of the limb—in this case, nerves for the hand and fingers—to other remaining muscles. When the subject tries to move their amputated limb, the reconnected muscle contracts. Those signals can then be connected to a computer to drive the motion of bionic hands.

The motion-sensing bionic arm and hands coordinate more naturally and fully with the brain by vibrating near the muscles, which creates sensations that help control the prosthesis.

The research study was funded in part by NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the NIH Director's Transformative Research Award. The award supports projects that are often risky and untested but have the potential to lead to major research findings.

"Decades of research have shown that muscles need to sense movement to work properly. This system basically hacks the neural circuits behind that system," says James W. Gnadt, Ph.D., of NINDS. "This approach takes the field of prosthetic medicine to a new level, which we hope will improve the lives of many."